From Soccer to Softball: The Rise and Fall of Ulster Stadium

Ulster Stadium hosted its first soccer game in the spring of 1925. Situated in the east end of Toronto, near Greenwood Avenue and Dundas Street, the stadium was built by the local soccer team Ulster United. Also known as the Red Handers, Ulster United was a team with deep Irish roots. The stadium would go on to host sporting games and events of all varieties for just under 20 years, until it was sold to a developer and houses were built in its place.

Ulster Stadium hosted everything from lacrosse and boxing matches to motorcycle and greyhound races. The stadium even hosted automobile stunts involving walls of flame. Fortunately no one died in these stunts, but one driver did suffer 1st degree burns attempting to drive a car over a ramp and through a ring of fire. They also held community events including an annual fife and drum band competition and weekly bingo nights put on by the Toronto Firefighters’ Association.

Organized soccer in 1920s Toronto looked like what we might call semi-pro sports today. The Red Handers were compensated in minor ways, receiving $2 (equivalent to $35 today), car fare, and an orange for each game they played, according to a former Ulster United supporter¹. Sometimes teams would even offer players jobs in exchange for joining their team. It wasn’t uncommon for workplaces to have teams in the types of leagues Ulster United was playing in. Even the TTC (Toronto’s transit agency) had a team, nicknamed the “Railwaymen”, that regularly played against Ulster United. Eaton, a power management company with a team of their own, is said to have sent recruiters to meet trains of immigrants from Europe at the station in the late 1920s. If they found a newcomer off the train who could dribble a soccer ball, they’d be given a job in exchange for playing on the company soccer team.

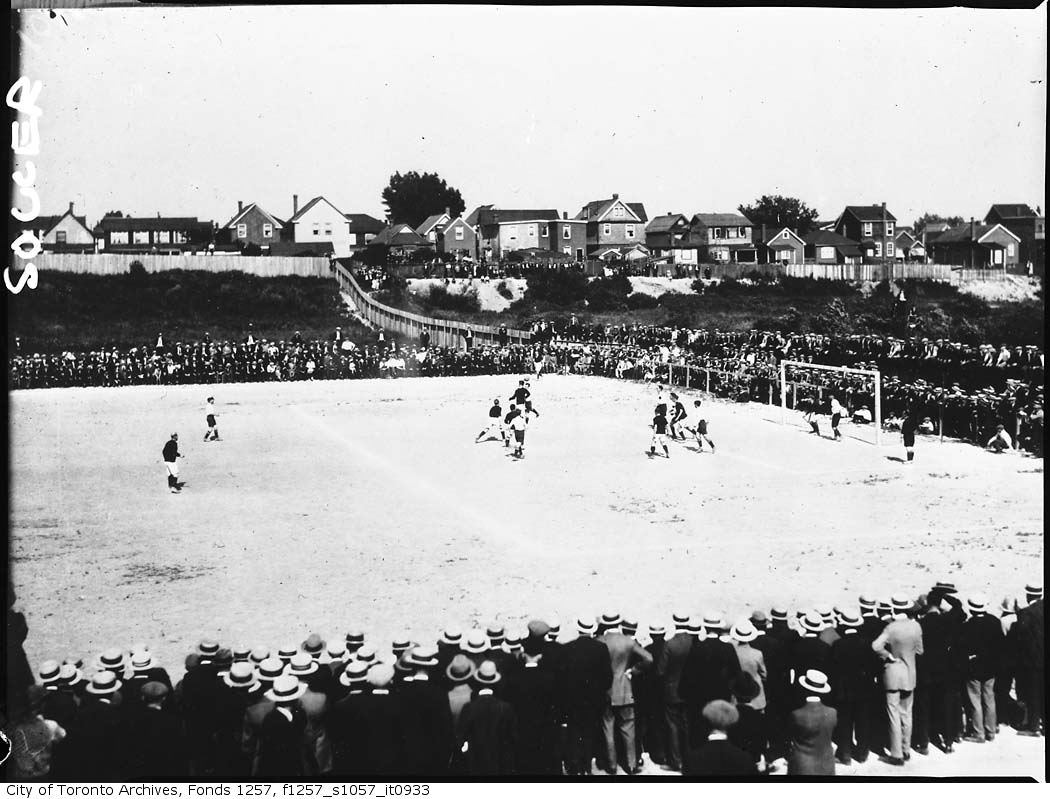

Soccer at Ulster Stadium in its early years (pre-1931, exact year unknown). Source: City of Toronto Archives

Soccer at Ulster Stadium in its early years (pre-1931, exact year unknown). Source: City of Toronto Archives

Soccer wasn’t the only sport where this was happening at the time. In women’s softball, too, players were enticed to join new teams by the promise of employment. Women would even sign contracts, referred to as “softball contracts” at the time, committing to play for a team for a period of time. Players would occasionally request to break a contract if another team offered them a better deal that included a job.

This practice was known to happen in the Danforth Women’s Senior Softball League, which held a short tenure at Ulster Stadium. They are the only women known to have played sports on those grounds, playing there twice a week during their 1928 season. The other stadium they played at, Viaduct Park, wasn’t always big enough to accommodate the crowds that would come to see them play.

Women’s softball games were ticketed events, and some of the teams in the senior leagues were considered professional at the time. According to a women’s sports columnist in 1933, the top players would receive up to “twenty pounds” a week². If we assume the author was referring to British pounds, that would be equivalent to almost £1,200 today, or $2,000 Canadian. While this report may have been exaggerated, even half that salary would’ve been enough to live off of in today’s economy. Another columnist in 1939, when asked if the women’s softball players in Toronto received salaries, responded that discussing salaries was taboo. However the columnist did share that players often received “merchandise vouchers” worth $15 for a season’s play, roughly $320 in today’s dollars.³

Women playing softball in 1924. Source: City of Toronto Archives

Women playing softball in 1924. Source: City of Toronto Archives

Despite the success of Ulster United, who regularly won league championships and cup trophies, the financials of the stadium weren’t always so strong. W.J. Pentland, the president of Ulster United who died tragically in a car accident in 1933, funded much of the operations out of his own pocket. Between 1930 and 1933, he was said to have spent $15,000 of his own money on the team and stadium, equivalent to almost $350,000 today.⁴

One larger expense spearheaded by W.J. Pentland was the introduction of floodlights. Ulster Stadium was the first in Toronto to host soccer games under floodlights. It was an exciting moment in local sports. The owners always had high hopes for the stadium and put great effort into maintaining and improving it. Unfortunately, floodlights and a passion for soccer wouldn’t be enough to save the stadium from the Depression years, and by as early as 1938 builders were inquiring about the property.

By 1942, the stadium was so far behind on its taxes that the city took possession of the property. It was bought a year later by Chester B. Sears, who intended to build on the beloved grounds. In a last ditch effort to save the stadium, the president of Ulster United raised funds to keep the stadium alive. He was successful, and the whole soccer team, and even the president himself, pitched in to get the stadium back in playing shape for another season. They mowed the lawns and fixed the fences themselves after a few months of neglect and vandalism left the stadium in subpar conditions. A year later, the City of Toronto would try its own hand at saving the stadium. They put in an offer to buy it, but it was rejected as it was $7,000 lower than the asking price of $33,000. Unfortunately for the Red Handers, the city wasn’t willing to go any higher.

In 1944, Chester B. Sears sold the stadium to the St. Lawrence Construction Co. Ltd., who converted the land into housing plots. Ulster United moved back to the Broadview YMCA field where they played before their stadium had been built. The Red Handers brought their passion for soccer to their new home, supplying both lights and seating for fans to improve the grounds. The floodlights of Ulster Stadium, however, didn’t come with them. They were sold to the Danforth Stadium, where softball was still played, shining a brighter light on the successors of the women who played at Ulster Stadium all those years before.

Today, only the entrance to Ulster Stadium remains, serving as a staircase between residential streets. The Ulster Arms tavern nearby, the old clubhouse of the Red Handers, is also still standing but has been boarded up for years. Its fate remains unknown.

The old entrance to Ulster Stadium. Source: Scrapbook Sports.

The old entrance to Ulster Stadium. Source: Scrapbook Sports.

Ulster Arms tavern as it stands in 2024. Source: Scrapbook Sports.

Ulster Arms tavern as it stands in 2024. Source: Scrapbook Sports.

References

¹Waring, E. (1967, Apr 14). Pros await start: Sponsors see minor loops as key to soccer success. The Globe and Mail (1936-) Retrieved from https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/pros-await-start/docview/1270028293/se-2

²Gibb, Alexandrine. (1933, Jul 29). No Man’s Land of Sport. Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) Retrieved from https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/page-10/docview/1434386870/se-2

³Rosenfeld, B. (1939, Jul 29). Feminine Sports Reel. The Globe and Mail (1936-) Retrieved from https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/feminine-sports/docview/1353828268/se-2

⁴Stop! Look! Listen! (1933, Feb 25). Toronto Daily Star (1900-1971) Retrieved from https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/page-14/docview/1433398622/se-2

Published: September 18, 2024

Updated: September 18, 2024